Posted on Wed, 07/15/2020 - 12:06

By Jess Harris, Director Communications, The Transition Accelerator

It’s no wonder that there is so much buzz around hydrogen when Canada and over 70 other countries need to find ways to drastically reduce emissions in order to reach their net-zero commitments by 2050. Hydrogen not only provides very low-carbon options for hard to decarbonize sectors like long distance transportation and steel and cement manufacturing, it also offers immense economic development and energy diversification benefits that make it a viable transition pathway that everyone can get behind.

The heavy-duty vehicle sector is an especially ideal market leader in a hydrogen economy because it currently relies on relatively high-priced fuel and has a large demand for energy that is frequent, predictable and concentrated. This suitability is bolstered by the industry being poised for disruption and receptive to innovation.

Whether the hydrogen is blue and made from fossil fuels paired with carbon capture and storage, or green and made from renewable energy sources, the fuel can be used in hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles with only water vapour being emitted from the tailpipe.

It is still early days for hydrogen fuel cell electric heavy-duty vehicles, but there are many lessons that Canada can learn from global efforts. The Transition Accelerator’s newest report explores the progress that has begun across the world to gain insights that can be applied in a Canadian context while evaluating the suitability of the technology for Canada’s trucking sector. Below, we interviewed one of the report’s authors, Jessica Lof from the Canadian Energy Systems Analysis Research (CESAR) Initiative at the University of Calgary, about the report’s findings and recommendations.

Why is hydrogen fuel a good fit to decarbonize the trucking sector?

Compared to diesel, there are many advantages that hydrogen can bring to the trucking sector, including eliminating harmful tailpipe emissions. When converted to electricity using a fuel cell to power an electric drivetrain, hydrogen also delivers the high torque and power desired to gain traction and accelerate with heavy loads. Anybody that has been stuck behind a big rig on a hill on a busy highway can appreciate the appeal.

Another great benefit is that the trucks are quiet and have low vibrations. They are also compatible with emerging innovations like autonomous vehicle technology. In an industry that is struggling to attract a younger labour force and improve profit margins, these are important qualities.

Are hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles a better option for the industry than plug-in battery electric vehicles?

Both options have electric drivetrains. There are transport segments that are well-suited to battery electric such as light or medium-duty urban operations. But, where hydrogen electric stands out is for long-distance, heavy weight or intensively used vehicles.

Hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles have near comparable vehicle weights to their diesel counterparts. On the other hand, a battery electric truck that is designed for long distances would need to be equipped with a large number of heavy batteries. When you add weight to the vehicle, it sacrifices allowable payload, and the company makes less money. In places like Canada, where transportation corridors are long and loads are heavy, there are major constraints on plug-in battery-electric options.

The other thing is refueling time. Hydrogen vehicles can refuel quickly. This means that when the trucks need to be refueled, the vehicles won’t be out of service for long. With battery electric trucks, there are usually lengthy recharge times required which aren’t compatible with the demands of the modern supply chain.

Why don’t we see any hydrogen fuel cell electric trucks on the road? What are the barriers to the widespread adoption of the technology?

In our survey, we identified a number of companies that are working to introduce hydrogen fuel cell electric heavy-duty trucks. For example, Nikola and Hyundai have already received a large number of orders for their trucks, but have yet to deliver them for large scale commercial deployment. Cummins, a major diesel engine manufacturer, recently purchased Hydrogenics, a Canadian hydrogen fuel cell company, showing that vehicle manufacturers know the direction the market is moving. Despite the apparent benefits of the technology for the trucking sector, hydrogen fuel cell electric trucks are still in the early stages of deployment around the world.

The absence of widespread adoption is not from a technology fit issue. It is due to the lack of hydrogen infrastructure which limits demand for hydrogen vehicles, keeping vehicle prices high and impacting the industry’s ability to gain experience with the technology. But with countries putting great effort into implementing hydrogen production and distribution infrastructure, deployment of fuel cell vehicles is expected to dramatically and quickly increase.

Places like Alberta that currently produce large amounts of hydrogen for industrial use are well-positioned to provide the fueling infrastructure. When you couple infrastructure with fuel demand from large heavy trucks in concentrated corridors, you have the conditions for success.

How can we overcome these barriers? What can we learn from other countries?

To advance the adoption of this vehicle technology while harnessing regional capacities to produce hydrogen fuel with minimal or no carbon emissions, the freight industry needs to gain experience with hydrogen fuel cell electric trucks under real world conditions. This will take some time, but is already happening around the world. This thinking was behind the launch of the Alberta Zero Emission Truck Electrification collaboration ( AZETEC) project, which is led by the Alberta Motor Transport Association. The industry wants to prove that the technology will work in the unique transportation conditions in Alberta, where we have cold weather, very heavy weights and long distances to travel. Other great examples include the H2Haul project that plans to test the technology for supermarket distribution needs in Europe and the ZANZEFF demonstration happening in the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

In addition, various gaps in regulations and standards need to be dealt with, which governments are already working hard to address. As in any market, continuous improvement opportunities should be invested in through research and development to bring component costs down.

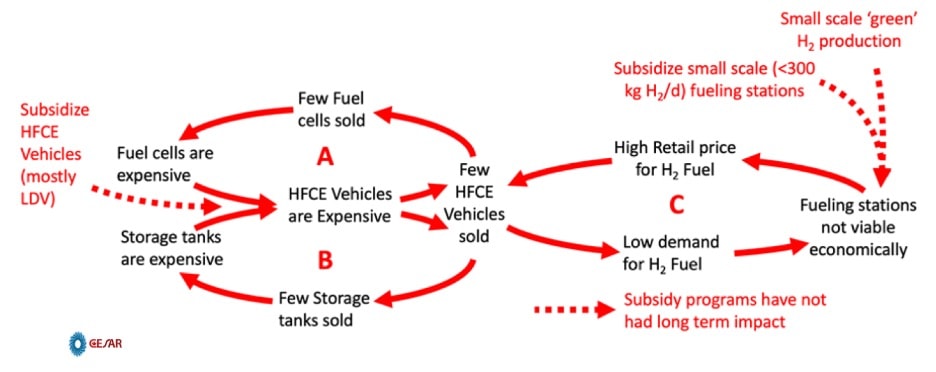

But ultimately, we need to achieve scale. Right now, we’re caught in a self-reinforcing vicious cycle. The cost of vehicles is high because there aren’t enough vehicles being made to support the cost of production. With few vehicles on the road, there is a low demand for hydrogen fuel. As a result, only low-capacity hydrogen fueling stations are set up and they are not very economical, which means the hydrogen fuel and infrastructure costs remain high.

The diagram above illustrates the current “vicious cycle” constraining hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles.

This is a problem that will continue on until we can achieve a scale where many trucks can be made and sold and where the prices of the fuel cells and tanks come down and the total cost of ownership rivals that of diesel trucks. Simultaneously, large-capacity fueling stations should be built to retail low-cost hydrogen, and be economically viable, creating a “virtuous cycle” where we have a self-sustaining positive feedback loop.

The diagram above illustrates the desired “virtuous cycle” supporting a hydrogen economy.

We can move towards a virtuous cycle by having deliberate commercialization strategies in regions with a competitive advantage, where low-cost hydrogen can be produced and there is a concentrated and assured demand for hydrogen from the transportation sector. Following this logic, Alberta’s Industrial Heartland Hydrogen Task Force is currently developing a framework to implement a hydrogen economy in the region.

Deliberate commercial deployments aimed at reaching this critical scale will require significant cross-sector collaboration, which is currently being seen around the world. In Switzerland, Hyundai has partnered with H2 Energy to produce hydrogen from hydropower and deploy 1600 heavy-duty vehicles. Germany’s HyLand-Hydrogen Regions program motivates consortiums from local regions to develop and implement integrated hydrogen transport concepts. The federal government is financially supporting 25 of these regional projects with grants ranging between 300,000 to 20 million euros each. And in Wuhan, China, a large fuel cell industrial park made up over 100 enterprises is being developed in coordination with the local automotive sector and industrial hydrogen supply networks to support the deployment of 10,000 – 30,000 buses, passenger cars, and commercial vehicles in the next five years.

Can government subsidies and policy help get these trucks on the road?

Yes. Subsidizing a fleet of hydrogen fuel cell electric heavy-duty vehicles and a high-capacity hydrogen fueling station in a concentrated region would help. But this has to be on a short-term basis until a higher scale of vehicles and infrastructure is achieved, so that we’re on a pathway to be economically viable without ongoing government subsidies.

Policies like the zero-emission vehicle standard that was just introduced in California can also help by encouraging manufacturers to integrate these vehicles into their production. Policies that provide preferential permits for high-traffic areas, like is done at the Ports in California and in Shanghai, could also help provide additional reasons to adopt the technology.

How does Canada’s progress compare to the rest of the world? Are we lagging behind?

We’re not lagging behind but we’re at risk of being leap-frogged. Canada is internationally renowned as a low-cost provider of very low or zero carbon hydrogen and a global leader in fuel cell innovation. For example, we are home to both Ballard and Hydrogenics, who are internationally-recognized manufacturers of fuel cells and electrolyzers. Alberta’s AZETEC project has set new bar for the size and travel distance for heavy-duty hydrogen fuel cell powered vehicles. In 2010, hydrogen fuel cell buses served the Vancouver Olympics and in 2005, Canada built and demonstrated the viability of a fuel cell parcel van. The new global interest in the zero-emission fuel positions our country for success if we can develop and deploy a hydrogen vision that goes beyond just the vehicles themselves and makes hydrogen a part of our national energy and environmental strategy.

There is so much opportunity with hydrogen. Other countries around the world like Germany, Australia, and Japan have announced their national strategies and are taking advantage of this opportunity. So, with great anticipation, we look forward to the Government of Canada’s hydrogen strategy that is expected by the end of the summer. Unless we recognize and position hydrogen as a key part of Canada’s future energy portfolio, we will be left behind and not realize the benefits of a hydrogen economy for both domestic and export markets, as countries like Australia have already started to do.